THE GARDENS OF DUMBARTON OAKS

Tucked away in a quiet part of Georgetown is Dumbarton Oaks, one of the finest American gardens still in existence. Inspired by her travels in Italy with her aunt Edith Wharton (author of Italian Villas and their Gardens), landscape gardener Beatrix Farrand created an American interpretation of the classical Mediterranean gardens she had studied, by carving out a series of garden rooms from the hilly terrain near Rock Creek for Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss, beginning in 1921.

Farrand designed a series of stone and brick walls, paths and steps, as well as arbors, trellises, pools and fountains. Although the layout was guided by Italian principles, she was influenced in her planting design by the English garden style, and Gertrude Jekyll, specifically.

Eleanor McPeck wrote in Beatrix Farrand’s American Landscapes, that Farrand’s trademarks were “clarity of outline, a strong sense of enclosure, the simple plan enriched by architectural detail and softened by perennial beds and trees.” The gardens of Dumbarton Oaks illustrate these principles beautifully.

My friend, Carolyn, standing in front of the north facade, below the French steps, on a cold day in February.

In 1941, after the estate was given to Harvard University, director John Thacher asked Farrand to write a guide for the garden’s care. Diane Kostial McGuire, in a foreward to Farrand’s Plant Book for Dumbarton Oaks, wrote that the book “resulted in this unique document that describes measures to be taken when plants need replacement, the various levels of maintenance required, the design concept of each part of the gardens, why particular choices were made, and why certain ideas were rejected.”

Below, a look at the gardens, as described by Beatrix Farrand in her Plant Book:

The Box Terrace (a revision by Ruth Havey eliminated the beautiful simplicity of the garden as envisioned by Farrand).

“The Box Terrace is intended to be an introductino to the Rose Garden, rather than a garden of importance on its own account. . . If the Box is allowed to grow too large it engulfs the scale of the terrace, which then tends to look more like a shelf than an overture to the Rose Garden.”

Lovers’ Lane pool and amphitheater. The seats were adapted from the “open-air theatre on the slopes of the Janiculum Hill at the Accademia degli Arcadi Bosco Parrasio. The shape of the theatre was copied from the one in Rome, but the slopes surrounding the Dumbarton theatre are far steeper than those on the Italian hillsides.”

“The whole arrangement surrounding the Lovers’ Lane pool is entirely controlled by the natural slopes of the ground and the deire to keep as many of the native trees as possible unhurt and undisturbed.”

“In order to give seclusion to this little theatre, it has been surrounded by cast-stone columns, baroque in design. . . The columns are connected with a split natural-wood lattice in long horizontal rectangles.”

“The composition of the planting of the Herbaceous Border should be rather carefully chosen from material which is somewhat unusual in its character and harmonious in its color tones.”

“The high wall, on the west side with its latticed-brick balustrade, shows the difference in the material thought appropriate to use on account of the added distance from the house and its more formal lines . . . This high wall is an admirable place on which to grow certain climbing Roses, perhaps a Magnolia grandiflora, Clematis paniculata, and a wispy veil of Forsythia suspensa narrowing the steps leading from the Box to the Rose Garden Terrace.”

Beatrix would not be happy to find her fountains so spotless and pristine. She wrote, “two fountains are kept filled and playing during the summer season, and it is important that their curbs be allowed to become as mossy as possible, as, scrubbed and cleaned well, the curbs would look new and fresh and garish, whereas the fountains should appear to have been ‘found’ there and to be a part of the old plan.”

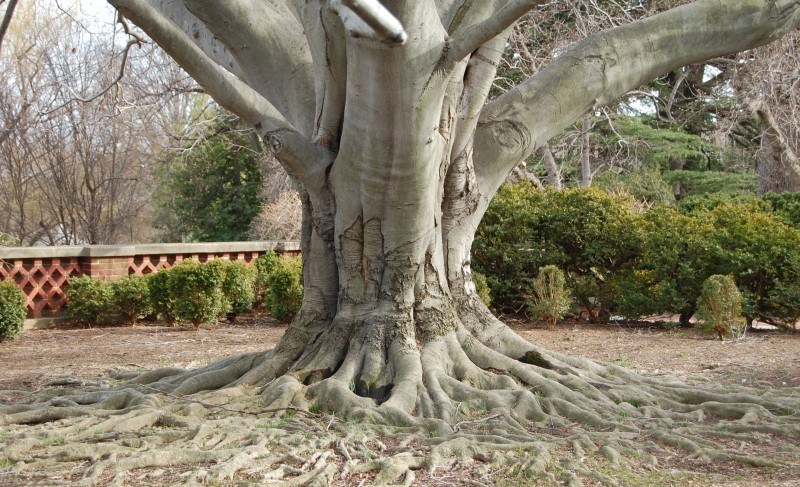

“. . . the structure of the tree (Fagus grandifolia) in winter is almost as beautiful as its summer color. It was clear that in any poistion so dominated by one magnificent tree, all the other planting must be secondary and as inconspicuous as possible.”

“The steps have been broken into three different flights in order to make the climbing not too laborious a process. Two-thirds of the way down the steps, a seat, under a lead canopy, is placed on the landing, and, when possible, is surrounded by pot [no, I don’t think she means THAT pot] plants which harmonize in color with those used in the garden.”

The irregular stones used in these beautiful steps signal that you are descending toward the “naturalistic” woodland and dell.

The Wisteria Arbor “was modified from a design of Du Cerceau (from his drawing of the garden of the Chateau Montargis). It is planted almost entirely with Wistaria, mainly of the lavender variety but with some few plants of white. The Wistaria Arbor is designed so as to be seen from below, so that the hanging clutches of the flowers will make a fragrant and lovely roof to the arbor.”

The orangery was built around 1810. Creeping Fig (Ficus pumila) climbs the walls and ceilings, and is pruned to form a pendant in front of each window.

Owner Mildred Bliss wrote, upon Beatrix Farrand’s death, “never did Beatrix Farrand impose on the land an arbitrary concept. She ‘listened’ to the light and wind and grade of each area under study. The gardens grew naturally from one another until now, in their luxuriant spring growth, as in the winter when leafless branches show each degree of distance and the naked masonry, there is a special quality of charming restfulness.”