It’s often said that winter is the perfect time to study your garden’s bones. As you do so, look up! Pay special attention to your garden’s vertical elements. Incorporating walls, fences, arbors, trellises, trees and shrubs can solve many problems and will add interest and beauty to your landscape.

SEPARATION

Whether you want to screen a driveway, gain a bit of privacy, or just provide transition from one garden space to another, vertical elements will do the job. A trellised fence takes up little space (depth) and provides a support for plants. In the picture above, Climbing Hydrangea (Hydrangea anomala subsp. petiolaris) covers a fence.

The tall picket fence and arched gate above tackle three issues: they create separation between front and back yards with a light touch, connect the buildings and provide support for roses.

At Dumbarton Oaks, below, a chain connected to stone pillars supports a Wisteria vine and creates a sense of enclosure.

In another area of the gardens at Dumbarton Oaks in Georgetown, Wisteria is pruned to frame the beautiful latticework that physically separates the amphitheatre, without visually screening it. Beatrix Farrand, who designed the gardens, was masterful in using vertical elements to shape the sloping land into separate terraced gardens with brilliant circulation from one garden to the next.

The latticed fence below, anchored by variegated Hosta, defines property lines and provides a connection between the neighbors’ gardens.

The front entrance, below, in this Kansas City neighborhood is beautifully defined by the stone and wrought iron fence and gate.

SEPARATION WITH PLANTS: This fruit tree in Lasham, England (I think it was a Pear), one of several along an axis, has been trained to bear fruit and separates the garden into two distinct spaces.

Charleston gardeners are some of the most talented vertical gardeners. In the picture below, the hedge, punctuated by a line of Palmettos, is an effective screen of the parking area. While the English gardener uses the fruit trees, above, only for definition, the Charleston hedge below is tasked with being a visually impenetrable screen.

I love the contrast in the English hedge below — tightly clipped (with flanking clipped sentries), yet with a fuzzy unkempt crown and surrounded by unmowed fields.

AN EXCUSE TO GROW PLANTS

Give a gardener a structure, and he or she will find a creative way to adorn it with plants. In the pictures below, a talented Princeton gardener espaliers Japanese Maples (Acer palmatum) and Japanese Hollies (Ilex crenata) on a humble cinderblock wall.

In the same Princeton garden, Climbing Hydrangea frames a window.

Below, trellises supporting roses complement the architecture and strengthen the symmetry of a formal garden.

No room to grow Figs or other fruit trees? Espalier them along a wall or strong fence, as is done below.

Below: Wall? What wall?

The pale pink and white Camellias (Camellia japonica) growing on the simple gothic trellises transform an otherwise empty weathered concrete wall along a Charleston driveway.

Below, roses smother a thatch-roofed cottage in Lasham, England.

Vertical features don’t just create enclosure and define boundaries. A tuteur or other plant support, like the one below sporting the native Passionflower Vine (Passiflora incarnata), acts as a focal point at Whilton, an exquisite garden near Charlottesville.

CANOPY

A mature tree canopy is an almost indispensable vertical element in the garden. Not only does it provide vertical interest, it offers shade and dappled light in the garden. In the pictures below, allees are used to define space, act as a guide to a destination and reinforce a strong axial line.

Dumbarton Oaks, above. Whilton, below.

Below, Plane Trees (Platanus x acerifolia) somewhere in Europe (9 years ago — can’t remember!). The width of the path is inexplicably out of scale with the allee.

What a beautiful “ceiling” the mature canopy makes at Dumbarton Oaks below.

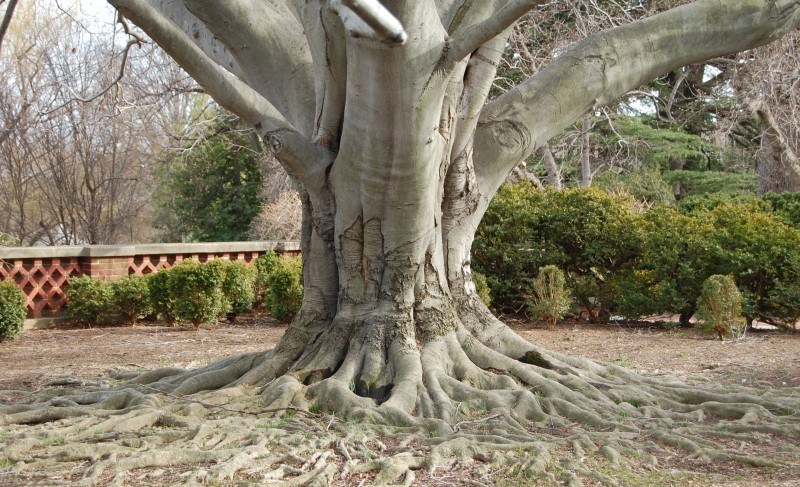

The native Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), below, is host to a Climbing Hydrangea. Never allow English Ivy (Hedera helix) to climb a tree. When growing any other vine, be sure to keep it under control, so that the vine does not inhibit the tree from producing the leaves necessary to thrive.

The streetscape in Savannah, below, gives me hope for urban planting. This strip bordering a commercial property was used to maximum effect. The evergreens were planted effectively between windows, then expertly pruned to frame the windows, show off the multi-trunk effect artfully against the pale wall, and allow pedestrians to pass below the canopies. They are underplanted with a simple ground cover.

And finally, have some fun with your vertical elements, as they did in the gardens at Whilton, below!

[custom-related-posts title=”Related Posts” none_text=”None found” order_by=”title” order=”ASC”]